History of WP&YR

WP&YR Facts

We invite you to share in the excitement of accomplishment in adventure and pioneering – of triumph over challenge– which is the story of the Klondike Gold Rush and the WP&YR. Click on a link to discover more about the White Pass & Yukon Route.

A Hoghead & His Hog

The old steam engines of the White Pass & Yukon Route guzzled enormous amounts of fuel and water as they worked their way over the summit of the White Pass. The railroaders called them “hogs” because of their insatiable fuel needs and an engineer was called a “hoghead.”

A famous engineer and hoghead, J.D. True, spent 40 years riding the rails and telling stories of his adventures. He recalls charging moose, runaway trains and snows higher than a train’s caboose.

A famous engineer and hoghead, J.D. True, spent 40 years riding the rails and telling stories of his adventures. He recalls charging moose, runaway trains and snows higher than a train’s caboose.

J.D. True filled two books with his adventure tales, now available at the WP&YR Train Shoppe in the Skagway Depot.

Civil Engineering Landmark

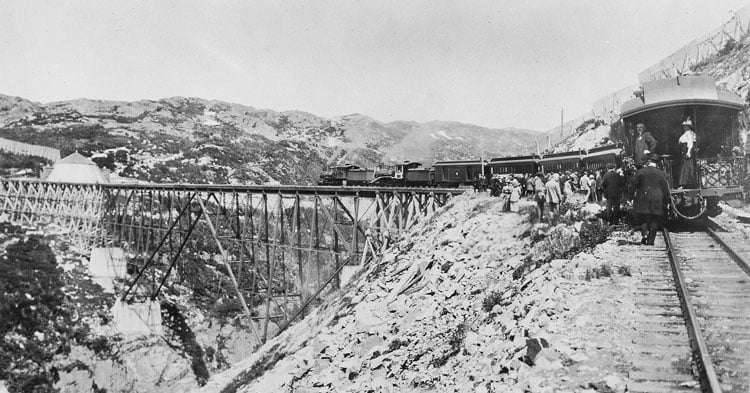

Photo: The Steel Cantilever Bridge

Depot Displays

Our history is on display in and around the Skagway depot and celebrates 106 years of WP&YR people, equipment, activities and art.

GOLD! GOLD! GOLD!

Born in the Klondike Gold Rush of 1898, the White Pass & Yukon Route is a rare story in the history of railroad building.

Every railroad has its own colorful beginnings. For the White Pass & Yukon Route, it was gold, discovered in 1896 by George Carmack and two Indian companions, Skookum Jim and Dawson Charlie.

The few flakes they found in Bonanza Creek in the Klondike barely filled the spent cartridge of a Winchester rifle. But it was enough to trigger an incredible stampede for riches: the Klondike Gold Rush.

“A Man of Vision”

The rush for riches was actually predicted by Skagway founder, Captain William Moore. He was hired by a Canadian survey party, headed by William Ogilvie who had been commissioned to map the 141st meridian, the boundary between the United States and Canada. Because the known route, Chilkoot Pass, was so rough and rugged, Moore and Skookum Jim decided to head north over unchartered ground and seek an easier route to the interior. They reached Lake Bennett, near the headwaters of the Yukon, and named the new potential route, White Pass, for the Canadian Minister of the Interior, Sir Thomas White.

Moore had a 160-acre homestead claim in Skagway. He returned to his home and began to think about the changes he felt would soon come. Search for gold in northwest Canada and Alaska had been underway for the past two decades and Moore believed that it was only a question of time before gold would be discovered. He built a sawmill, a wharf and blazed the trail to the summit of the White Pass. Moore even suggested to his son that eventually there would be a railroad through to the lakes and to prepare for the coming gold rush.

The Rush to the Klondike Begins

The headline of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer on July 17, 1897 broadcast the news of the discovery of gold in the Canadian Klondike. Under headlines “Gold! Gold! Gold!” the newspaper reported that “Sixty Eight Rich Men on the Steamer Portland” arrived in Seattle with “Stacks of Yellow Metal”.

The news spread like wildfire and the country, in the midst of a depression, went gold crazy. Tens of thousands of gold crazed men and women steamed up the Inside Passage waterway and arrived in Dyea and Skagway to begin the overland trek to the Klondike. Six hundred miles over treacherous and dangerous trails and waterways lay before them.

Choices To Be Made

Both the Chilkoot Trail and the White Pass Trail were filled with hazards and harrowing experiences. Three thousand horses died on the White Pass Trail because of the tortures of the trail and the inexperience of the stampeders.

Men immediately began to think of easier ways to travel to the Klondike. In the fall of 1897 George Brackett, a former construction engineer on the Northern Pacific Railroad, built a twelve mile toll road up the canyon of the White Pass.

The toll gates were ignored by travelers and Brackett’s road was a failure.

THE WP&YR STORY BEGINS

“… a Railroad to Hell”

They met by chance in Skagway, talked through the night and by dawn the railroad project was no longer a dream but an accepted reality. It was a meeting of money, talent and vision.

The White Pass & Yukon Railroad Company, organized in April, 1898, paid Brackett $60,000 for the right-of-way to his road. And on May 28, 1898 construction began on a narrow gauge railroad.

Constructed Against All Odds

On July 21, 1898, two months after construction began, the railroad’s first engine went into service over the first four miles of completed track. The WP&YR was the northernmost railroad in the Western Hemisphere.

Building the one hundred and ten miles of track was a challenge in every way. Construction required cliff hanging turns of 16 degrees, building two tunnels and numerous bridges and trestles. Work on the tunnel at Mile 16 took place in the dead of winter with heavy snow and temperatures as low as 60 below slowed the work. The workers reached the summit of White Pass on February 20, 1899 and by July 6, 1899 construction reached Lake Bennett and the beginning of the river and lakes route.

While construction crews battled their way north laying rail, another crew came from the north heading south and together they met on July 29, 1900 in Carcross where a ceremonial golden spike was driven by Samuel H. Graves, the president of the railroad. Thirty five thousand men worked on the construction of the railroad – some for a day, others for a longer period but all shared in the dream and the hardship.

The $10 million project was the product of British financing, American engineering and Canadian contracting. Tens of thousands of men and 450 tons of explosives overcame harsh and challenging climate and geography to create the “Railway Built of Gold.”

Life After The Gold Rush

The railroad was operated by steam until 1954 when the transition came to diesel electric motive power. White Pass matured into a fully-integrated transportation company operating docks, trains, stage coaches, sleighs, buses, paddle wheelers, trucks, ships, airplanes, hotels and pipelines.

World metal prices plummeted in 1982, mines closed and the WP&YR suspended operations. It reopened in 1988 to operate as a narrow gauge excursion railroad.

The Adventure Continues

The end of the story of one of history’s dynamic events: the Klondike Gold Rush.

One hundred thousand men and women headed north but only 30,000 or 40,000 actually reached the gold fields of the Klondike. Four thousand or so prospectors found the gold but only a few hundred became rich.

What about the discoverers of the gold? George Carmack, Skookum Jim and Dawson Charlie! Carmack’s gold allowed him to have a more adventurous life with two wives, and investment in real estate in Seattle and California. Dawson Charlie sold his mining properties and spent his years in Carcross.

Skookum Jim continued as a prospector and died rich but worn out from his hardy life.

For one hundred years the White Pass & Yukon Route has been an economic lifeline to the north. Freight and passengers moved about the north with ease and the railroad adapted to the changing times. It was the ability to adapt that kept it going – from freight, stampeders and gold to movement of ores and concentrates to tourism – each has been embraced and has given the railroad a new mission in the north.

“On To Alaska With Buchanan”

For fifteen years groups of approximately 50 young people, mostly boys, made the annual summer excursion from Detroit to Alaska. The travelers departed from Detroit in mid-July traveling first class by train across Canada to Vancouver B.C. and Puget Sound. Three days on a steamer and then arrival in Skagway. They boarded the White Pass & Yukon Railroad to travel to the lake country and then a transfer by boat to Atlin.

The young folks, dressed in coat and tie, had to be on their best behavior. Many years later members of the various Buchanan Boys groups returned to Skagway to ride the WP&YR and to revisit the memories of their special and happy trips. Reportedly the boys from one of the summer trips painted the sign “On To Alaska With Buchanan” on the side of the mountain to commemorate their inspiring leader, George Buchanan.

Vision Triumphs over Challenge

Because of this uncertainty the White Pass & Yukon Route decided to incorporate construction in three companies so that the laws of the USA and Canada were obeyed. In Alaska, the railroad was incorporated as Pacific and Arctic Railway & Navigation Company and today still operates under that legal identity. The British Columbia Yukon Railway Company and the British Yukon Railway Company were incorporated in British Columbia and Yukon respectively, with all three companies incorporated in 1898. White Pass & Yukon Route served as an umbrella to coordinate the three entities’ operations.

During the twenty six months of construction the company was challenged by climate, geography and labor issues – all of which translated into soaring construction costs. Nearly all the work between Skagway and the Summit was through solid rock. Dynamite had not yet come into use and immense quantities of black powder were used for blasting. The mountain sides were so steep that the men had to be suspended by ropes to prevent them falling off while cutting the grade. During construction, 35,000 men worked on the railway, and 35 lost their lives.

But Close Brothers of London, under the leadership of W.B. Close, stayed the course, spent $10,000,000 on construction of the railroad. Close Brothers owned White Pass & Yukon Route until 1951 when it was sold to Canadian investors. Close Brothers prospers still today as the largest independent quoted merchant bank in the UK and one of the 200 largest companies by market capitalization listed on the London Stock Exchange.

Skagway

Skagway got its name from the Tlingit (Indian) name “Skagua” which means “the place where the north wind blows”. The maritime climate brings cool summers and mild winters. Average summer temperatures range from 45º-67º F.; winter temperatures average 18º-37º F. Within the shadow of the mountains, Skagway receives less rain than is typical of Southeast Alaska, averaging 26 inches of rain per year, and 39 inches of snow.

The first non-Native settler was Captain William Moore in 1887, who is credited with the discovery of the White Pass route into Interior Canada. In July 1897, gold was discovered in the Klondike, and the first boatload of prospectors landed. By October 1897, according to a Northwest Mounted Police Report, Skagway “had grown from a concourse of tents to a fair-sized town with well-laid-out streets and numerous frame buildings, stores, saloons, gambling houses, dance houses and a population of about 20,000”.

Skagway became the first incorporated City in Alaska in 1900; its population was 3,117 at that time, the second-largest settlement in Alaska.

Skagway is now a restored gold rush town and headquarters of the Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park.

For more information on Skagway visit www.skagway.com.

Living History

In September of 2002, Earl F. Benedict came to Skagway by cruise ship and rode the White Pass & Yukon Route for the first time. He was retracing the steps of his grandfather, who worked for the WP&YR more than a hundred years ago.

While reading the All Aboard magazine, he saw a photo of his grandfather which he had seen in his family’s photo albums! After the train ride, Earl came into the WP&YR offices to share his stories and memories.

Upon returning home, Earl reviewed some of the historical artifacts in his possession and made copies of rare photos and documents for the WP&YR.

Earl Benedict’s visit to Skagway began a new relationship that helps celebrate the living history of the WP&YR!

Maintenance Of Way

Track maintenance using specialized equipment is an important job for WP&YR.

Tamper: picks up the rail as metal teeth vibrate into the ground to pack the ballast, (right of way gravel). Also works as a liner, which uses lasers to indicate track level and curvatures.

Ballast regulator: distributes the ballast evenly and brushes the track after the job is done.

Tie crane: inserts and extracts the ties.

Casey car: used to inspect the line every morning for clearance to begin the day’s excursions.

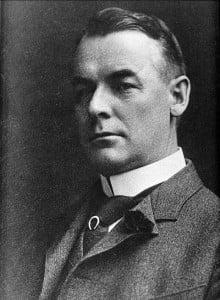

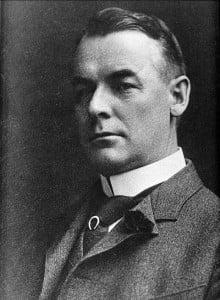

Michael J. Heney

The partnership between Heney and the men who would become his friends and colleagues in the construction of the railroad was successful. The White Pass & Yukon Route was built in twenty-six months for ten million dollars. The “Scenic Railway of the World” secured Heney’s place in history.

Pay Dirt!

In only five months, between July and November of 1898, the United States mints in Seattle and San Francisco received ten million dollars worth of Klondike Gold. By 1900, another thirty-eight million had been recorded–the result of the largest gold rush the world has ever known!

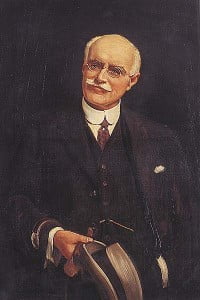

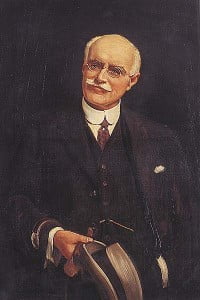

Railroad Builders

Samuel Graves was president of the railroad from 1898 until 1911. He worked with the Close Brothers Bank of London to finance construction. John Hislop and E.C. Hawkins were surveyors and design engineers for the construction. Michael J. Heney was the labor contractor and manager of the workers who placed the dynamite, laid the rails, built bridges and tunnels and made the dream into reality.

Rolling Stock

The WP&YR rail fleet consists of twenty diesel-electric locomotives, 69 restored and replica passenger coaches and two steam locomotives. The diesel-electric locomotives are General Electric units dating back to the 1950s and ALCO units from the 1960s.

The pride of the fleet is Engine No. 73, a fully restored 1947 Baldwin 2-8-2 Mikado class steam locomotive and was joined by No. 69 in 2005, a Baldwin 2-8-0 built for WP&YR in 1907.

The WP&YR passenger coaches are named after lakes and rivers in Alaska, Yukon and British Columbia and are on average 49 years old. The oldest car, Lake Emerald, was built in 1883 and is on the line each day. Lake Tutshi, vintage 1893, starred in the 1935 Universal Studios movie “Diamond Jim Brady.” And the Lake Lebarge carried Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip on a royal tour out of Whitehorse in 1959.

Rotary Snowplow No. 1

Rotary Snowplow No. 1 was built in 1898 by the Cooke Locomotive and Machinery Company of Paterson, New Jersey for WP&YR.

It helped the railroad face the challenges of heavy winter snows with accumulations of up to 12 feet. Pushed by up to 2 helper engines, the rotary’s 10 huge blades sent snow flying out to the side of the tracks by centrifugal force. It was retired in 1965 but was used as recently as 2001 for a ceremonial clearing of the rails. Rotary Snowplow No. 1 has been restored and can be seen by the Skagway Depot.

The White Pass “Spirit”

The White Pass & Yukon Route (WP&YR) is symbolic of triumph over challenge. The railroad was considered an impossible task but it was literally blasted through coastal mountains in only 26 months over a century ago. Tens of thousands of men with picks and shovels and 450 tons of explosives overcame harsh climate and challenging geography to create “the railway built of gold”.

But, the zenith of the Klondike Gold Rush had passed by the time the railroad was completed. Despite conquering the significant snowfalls with the rotary snowplow and spanning Dead Horse Gulch with the tallest cantilever bridge in the world at the time, it was time to diversify to survive. The WP&YR evolved to encompass wharves, stage lines, paddlewheelers, hotels, aircraft, buses, pipelines, trucks and ships to cater to emerging market conditions.

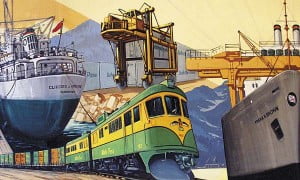

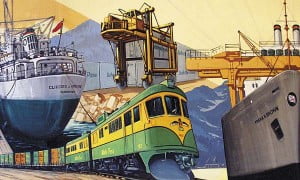

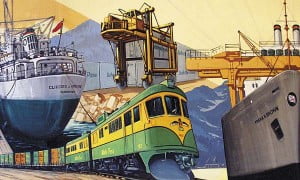

Self-sufficiency and the need for continuous progress made innovation a hallmark of WP&YR operations. WP&YR pioneered the “Container Route” – the inter-modal movement of containers by ship, train and truck in 1955. In 1988, the company reinvented itself as a tourist attraction for a tourism market after shutting down as a fully integrated transportation company 7 years earlier.

Since 1898, WP&YR’s survival and prosperity has been based on the spirit of accomplishment in the face of adversity.

WP&YR Facts

We invite you to share in the excitement of accomplishment in adventure and pioneering – of triumph over challenge– which is the story of the Klondike Gold Rush and the WP&YR. Click on a link to discover more about the White Pass & Yukon Route.

A Hoghead & His Hog

The old steam engines of the White Pass & Yukon Route guzzled enormous amounts of fuel and water as they worked their way over the summit of the White Pass. The railroaders called them “hogs” because of their insatiable fuel needs and an engineer was called a “hoghead.”

A famous engineer and hoghead, J.D. True, spent 40 years riding the rails and telling stories of his adventures. He recalls charging moose, runaway trains and snows higher than a train’s caboose.

A famous engineer and hoghead, J.D. True, spent 40 years riding the rails and telling stories of his adventures. He recalls charging moose, runaway trains and snows higher than a train’s caboose.

J.D. True filled two books with his adventure tales, now available at the WP&YR Train Shoppe in the Skagway Depot.

Civil Engineering Landmark

Photo: The Steel Cantilever Bridge

Depot Displays

Our history is on display in and around the Skagway depot and celebrates 106 years of WP&YR people, equipment, activities and art.

GOLD! GOLD! GOLD!

Born in the Klondike Gold Rush of 1898, the White Pass & Yukon Route is a rare story in the history of railroad building.

Every railroad has its own colorful beginnings. For the White Pass & Yukon Route, it was gold, discovered in 1896 by George Carmack and two Indian companions, Skookum Jim and Dawson Charlie.

The few flakes they found in Bonanza Creek in the Klondike barely filled the spent cartridge of a Winchester rifle. But it was enough to trigger an incredible stampede for riches: the Klondike Gold Rush.

“A Man of Vision”

The rush for riches was actually predicted by Skagway founder, Captain William Moore. He was hired by a Canadian survey party, headed by William Ogilvie who had been commissioned to map the 141st meridian, the boundary between the United States and Canada. Because the known route, Chilkoot Pass, was so rough and rugged, Moore and Skookum Jim decided to head north over unchartered ground and seek an easier route to the interior. They reached Lake Bennett, near the headwaters of the Yukon, and named the new potential route, White Pass, for the Canadian Minister of the Interior, Sir Thomas White.

Moore had a 160-acre homestead claim in Skagway. He returned to his home and began to think about the changes he felt would soon come. Search for gold in northwest Canada and Alaska had been underway for the past two decades and Moore believed that it was only a question of time before gold would be discovered. He built a sawmill, a wharf and blazed the trail to the summit of the White Pass. Moore even suggested to his son that eventually there would be a railroad through to the lakes and to prepare for the coming gold rush.

The Rush to the Klondike Begins

The headline of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer on July 17, 1897 broadcast the news of the discovery of gold in the Canadian Klondike. Under headlines “Gold! Gold! Gold!” the newspaper reported that “Sixty Eight Rich Men on the Steamer Portland” arrived in Seattle with “Stacks of Yellow Metal”.

The news spread like wildfire and the country, in the midst of a depression, went gold crazy. Tens of thousands of gold crazed men and women steamed up the Inside Passage waterway and arrived in Dyea and Skagway to begin the overland trek to the Klondike. Six hundred miles over treacherous and dangerous trails and waterways lay before them.

Choices To Be Made

Both the Chilkoot Trail and the White Pass Trail were filled with hazards and harrowing experiences. Three thousand horses died on the White Pass Trail because of the tortures of the trail and the inexperience of the stampeders.

Men immediately began to think of easier ways to travel to the Klondike. In the fall of 1897 George Brackett, a former construction engineer on the Northern Pacific Railroad, built a twelve mile toll road up the canyon of the White Pass.

The toll gates were ignored by travelers and Brackett’s road was a failure.

THE WP&YR STORY BEGINS

“… a Railroad to Hell”

They met by chance in Skagway, talked through the night and by dawn the railroad project was no longer a dream but an accepted reality. It was a meeting of money, talent and vision.

The White Pass & Yukon Railroad Company, organized in April, 1898, paid Brackett $60,000 for the right-of-way to his road. And on May 28, 1898 construction began on a narrow gauge railroad.

Constructed Against All Odds

On July 21, 1898, two months after construction began, the railroad’s first engine went into service over the first four miles of completed track. The WP&YR was the northernmost railroad in the Western Hemisphere.

Building the one hundred and ten miles of track was a challenge in every way. Construction required cliff hanging turns of 16 degrees, building two tunnels and numerous bridges and trestles. Work on the tunnel at Mile 16 took place in the dead of winter with heavy snow and temperatures as low as 60 below slowed the work. The workers reached the summit of White Pass on February 20, 1899 and by July 6, 1899 construction reached Lake Bennett and the beginning of the river and lakes route.

While construction crews battled their way north laying rail, another crew came from the north heading south and together they met on July 29, 1900 in Carcross where a ceremonial golden spike was driven by Samuel H. Graves, the president of the railroad. Thirty five thousand men worked on the construction of the railroad – some for a day, others for a longer period but all shared in the dream and the hardship.

The $10 million project was the product of British financing, American engineering and Canadian contracting. Tens of thousands of men and 450 tons of explosives overcame harsh and challenging climate and geography to create the “Railway Built of Gold.”

Life After The Gold Rush

The railroad was operated by steam until 1954 when the transition came to diesel electric motive power. White Pass matured into a fully-integrated transportation company operating docks, trains, stage coaches, sleighs, buses, paddle wheelers, trucks, ships, airplanes, hotels and pipelines.

World metal prices plummeted in 1982, mines closed and the WP&YR suspended operations. It reopened in 1988 to operate as a narrow gauge excursion railroad.

The Adventure Continues

The end of the story of one of history’s dynamic events: the Klondike Gold Rush.

One hundred thousand men and women headed north but only 30,000 or 40,000 actually reached the gold fields of the Klondike. Four thousand or so prospectors found the gold but only a few hundred became rich.

What about the discoverers of the gold? George Carmack, Skookum Jim and Dawson Charlie! Carmack’s gold allowed him to have a more adventurous life with two wives, and investment in real estate in Seattle and California. Dawson Charlie sold his mining properties and spent his years in Carcross.

Skookum Jim continued as a prospector and died rich but worn out from his hardy life.

For one hundred years the White Pass & Yukon Route has been an economic lifeline to the north. Freight and passengers moved about the north with ease and the railroad adapted to the changing times. It was the ability to adapt that kept it going – from freight, stampeders and gold to movement of ores and concentrates to tourism – each has been embraced and has given the railroad a new mission in the north.

“On To Alaska With Buchanan”

For fifteen years groups of approximately 50 young people, mostly boys, made the annual summer excursion from Detroit to Alaska. The travelers departed from Detroit in mid-July traveling first class by train across Canada to Vancouver B.C. and Puget Sound. Three days on a steamer and then arrival in Skagway. They boarded the White Pass & Yukon Railroad to travel to the lake country and then a transfer by boat to Atlin.

The young folks, dressed in coat and tie, had to be on their best behavior. Many years later members of the various Buchanan Boys groups returned to Skagway to ride the WP&YR and to revisit the memories of their special and happy trips. Reportedly the boys from one of the summer trips painted the sign “On To Alaska With Buchanan” on the side of the mountain to commemorate their inspiring leader, George Buchanan.

Vision Triumphs over Challenge

Because of this uncertainty the White Pass & Yukon Route decided to incorporate construction in three companies so that the laws of the USA and Canada were obeyed. In Alaska, the railroad was incorporated as Pacific and Arctic Railway & Navigation Company and today still operates under that legal identity. The British Columbia Yukon Railway Company and the British Yukon Railway Company were incorporated in British Columbia and Yukon respectively, with all three companies incorporated in 1898. White Pass & Yukon Route served as an umbrella to coordinate the three entities’ operations.

During the twenty six months of construction the company was challenged by climate, geography and labor issues – all of which translated into soaring construction costs. Nearly all the work between Skagway and the Summit was through solid rock. Dynamite had not yet come into use and immense quantities of black powder were used for blasting. The mountain sides were so steep that the men had to be suspended by ropes to prevent them falling off while cutting the grade. During construction, 35,000 men worked on the railway, and 35 lost their lives.

But Close Brothers of London, under the leadership of W.B. Close, stayed the course, spent $10,000,000 on construction of the railroad. Close Brothers owned White Pass & Yukon Route until 1951 when it was sold to Canadian investors. Close Brothers prospers still today as the largest independent quoted merchant bank in the UK and one of the 200 largest companies by market capitalization listed on the London Stock Exchange.

Skagway

Skagway got its name from the Tlingit (Indian) name “Skagua” which means “the place where the north wind blows”. The maritime climate brings cool summers and mild winters. Average summer temperatures range from 45º-67º F.; winter temperatures average 18º-37º F. Within the shadow of the mountains, Skagway receives less rain than is typical of Southeast Alaska, averaging 26 inches of rain per year, and 39 inches of snow.

The first non-Native settler was Captain William Moore in 1887, who is credited with the discovery of the White Pass route into Interior Canada. In July 1897, gold was discovered in the Klondike, and the first boatload of prospectors landed. By October 1897, according to a Northwest Mounted Police Report, Skagway “had grown from a concourse of tents to a fair-sized town with well-laid-out streets and numerous frame buildings, stores, saloons, gambling houses, dance houses and a population of about 20,000”.

Skagway became the first incorporated City in Alaska in 1900; its population was 3,117 at that time, the second-largest settlement in Alaska.

Skagway is now a restored gold rush town and headquarters of the Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park.

For more information on Skagway visit www.skagway.com.

Living History

In September of 2002, Earl F. Benedict came to Skagway by cruise ship and rode the White Pass & Yukon Route for the first time. He was retracing the steps of his grandfather, who worked for the WP&YR more than a hundred years ago.

While reading the All Aboard magazine, he saw a photo of his grandfather which he had seen in his family’s photo albums! After the train ride, Earl came into the WP&YR offices to share his stories and memories.

Upon returning home, Earl reviewed some of the historical artifacts in his possession and made copies of rare photos and documents for the WP&YR.

Earl Benedict’s visit to Skagway began a new relationship that helps celebrate the living history of the WP&YR!

Maintenance Of Way

Track maintenance using specialized equipment is an important job for WP&YR.

Tamper: picks up the rail as metal teeth vibrate into the ground to pack the ballast, (right of way gravel). Also works as a liner, which uses lasers to indicate track level and curvatures.

Ballast regulator: distributes the ballast evenly and brushes the track after the job is done.

Tie crane: inserts and extracts the ties.

Casey car: used to inspect the line every morning for clearance to begin the day’s excursions.

Michael J. Heney

The partnership between Heney and the men who would become his friends and colleagues in the construction of the railroad was successful. The White Pass & Yukon Route was built in twenty-six months for ten million dollars. The “Scenic Railway of the World” secured Heney’s place in history.

Pay Dirt!

In only five months, between July and November of 1898, the United States mints in Seattle and San Francisco received ten million dollars worth of Klondike Gold. By 1900, another thirty-eight million had been recorded–the result of the largest gold rush the world has ever known!

Railroad Builders

Samuel Graves was president of the railroad from 1898 until 1911. He worked with the Close Brothers Bank of London to finance construction. John Hislop and E.C. Hawkins were surveyors and design engineers for the construction. Michael J. Heney was the labor contractor and manager of the workers who placed the dynamite, laid the rails, built bridges and tunnels and made the dream into reality.

Rolling Stock

The WP&YR rail fleet consists of twenty diesel-electric locomotives, 69 restored and replica passenger coaches and two steam locomotives. The diesel-electric locomotives are General Electric units dating back to the 1950s and ALCO units from the 1960s.

The pride of the fleet is Engine No. 73, a fully restored 1947 Baldwin 2-8-2 Mikado class steam locomotive and was joined by No. 69 in 2005, a Baldwin 2-8-0 built for WP&YR in 1907.

The WP&YR passenger coaches are named after lakes and rivers in Alaska, Yukon and British Columbia and are on average 49 years old. The oldest car, Lake Emerald, was built in 1883 and is on the line each day. Lake Tutshi, vintage 1893, starred in the 1935 Universal Studios movie “Diamond Jim Brady.” And the Lake Lebarge carried Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip on a royal tour out of Whitehorse in 1959.

Rotary Snowplow No. 1

Rotary Snowplow No. 1 was built in 1898 by the Cooke Locomotive and Machinery Company of Paterson, New Jersey for WP&YR.

It helped the railroad face the challenges of heavy winter snows with accumulations of up to 12 feet. Pushed by up to 2 helper engines, the rotary’s 10 huge blades sent snow flying out to the side of the tracks by centrifugal force. It was retired in 1965 but was used as recently as 2001 for a ceremonial clearing of the rails. Rotary Snowplow No. 1 has been restored and can be seen by the Skagway Depot.

The White Pass “Spirit”

The White Pass & Yukon Route (WP&YR) is symbolic of triumph over challenge. The railroad was considered an impossible task but it was literally blasted through coastal mountains in only 26 months over a century ago. Tens of thousands of men with picks and shovels and 450 tons of explosives overcame harsh climate and challenging geography to create “the railway built of gold”.

But, the zenith of the Klondike Gold Rush had passed by the time the railroad was completed. Despite conquering the significant snowfalls with the rotary snowplow and spanning Dead Horse Gulch with the tallest cantilever bridge in the world at the time, it was time to diversify to survive. The WP&YR evolved to encompass wharves, stage lines, paddlewheelers, hotels, aircraft, buses, pipelines, trucks and ships to cater to emerging market conditions.

Self-sufficiency and the need for continuous progress made innovation a hallmark of WP&YR operations. WP&YR pioneered the “Container Route” – the inter-modal movement of containers by ship, train and truck in 1955. In 1988, the company reinvented itself as a tourist attraction for a tourism market after shutting down as a fully integrated transportation company 7 years earlier.

Since 1898, WP&YR’s survival and prosperity has been based on the spirit of accomplishment in the face of adversity.

WP&YR Facts

We invite you to share in the excitement of accomplishment in adventure and pioneering – of triumph over challenge– which is the story of the Klondike Gold Rush and the WP&YR. Click on a link to discover more about the White Pass & Yukon Route.

A Hoghead & His Hog

The old steam engines of the White Pass & Yukon Route guzzled enormous amounts of fuel and water as they worked their way over the summit of the White Pass. The railroaders called them “hogs” because of their insatiable fuel needs and an engineer was called a “hoghead.”

A famous engineer and hoghead, J.D. True, spent 40 years riding the rails and telling stories of his adventures. He recalls charging moose, runaway trains and snows higher than a train’s caboose.

A famous engineer and hoghead, J.D. True, spent 40 years riding the rails and telling stories of his adventures. He recalls charging moose, runaway trains and snows higher than a train’s caboose.

J.D. True filled two books with his adventure tales, now available at the WP&YR Train Shoppe in the Skagway Depot.

Civil Engineering Landmark

Photo: The Steel Cantilever Bridge

Depot Displays

Our history is on display in and around the Skagway depot and celebrates 106 years of WP&YR people, equipment, activities and art.

GOLD! GOLD! GOLD!

Born in the Klondike Gold Rush of 1898, the White Pass & Yukon Route is a rare story in the history of railroad building.

Every railroad has its own colorful beginnings. For the White Pass & Yukon Route, it was gold, discovered in 1896 by George Carmack and two Indian companions, Skookum Jim and Dawson Charlie.

The few flakes they found in Bonanza Creek in the Klondike barely filled the spent cartridge of a Winchester rifle. But it was enough to trigger an incredible stampede for riches: the Klondike Gold Rush.

“A Man of Vision”

The rush for riches was actually predicted by Skagway founder, Captain William Moore. He was hired by a Canadian survey party, headed by William Ogilvie who had been commissioned to map the 141st meridian, the boundary between the United States and Canada. Because the known route, Chilkoot Pass, was so rough and rugged, Moore and Skookum Jim decided to head north over unchartered ground and seek an easier route to the interior. They reached Lake Bennett, near the headwaters of the Yukon, and named the new potential route, White Pass, for the Canadian Minister of the Interior, Sir Thomas White.

Moore had a 160-acre homestead claim in Skagway. He returned to his home and began to think about the changes he felt would soon come. Search for gold in northwest Canada and Alaska had been underway for the past two decades and Moore believed that it was only a question of time before gold would be discovered. He built a sawmill, a wharf and blazed the trail to the summit of the White Pass. Moore even suggested to his son that eventually there would be a railroad through to the lakes and to prepare for the coming gold rush.

The Rush to the Klondike Begins

The headline of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer on July 17, 1897 broadcast the news of the discovery of gold in the Canadian Klondike. Under headlines “Gold! Gold! Gold!” the newspaper reported that “Sixty Eight Rich Men on the Steamer Portland” arrived in Seattle with “Stacks of Yellow Metal”.

The news spread like wildfire and the country, in the midst of a depression, went gold crazy. Tens of thousands of gold crazed men and women steamed up the Inside Passage waterway and arrived in Dyea and Skagway to begin the overland trek to the Klondike. Six hundred miles over treacherous and dangerous trails and waterways lay before them.

Choices To Be Made

Both the Chilkoot Trail and the White Pass Trail were filled with hazards and harrowing experiences. Three thousand horses died on the White Pass Trail because of the tortures of the trail and the inexperience of the stampeders.

Men immediately began to think of easier ways to travel to the Klondike. In the fall of 1897 George Brackett, a former construction engineer on the Northern Pacific Railroad, built a twelve mile toll road up the canyon of the White Pass.

The toll gates were ignored by travelers and Brackett’s road was a failure.

THE WP&YR STORY BEGINS

“… a Railroad to Hell”

They met by chance in Skagway, talked through the night and by dawn the railroad project was no longer a dream but an accepted reality. It was a meeting of money, talent and vision.

The White Pass & Yukon Railroad Company, organized in April, 1898, paid Brackett $60,000 for the right-of-way to his road. And on May 28, 1898 construction began on a narrow gauge railroad.

Constructed Against All Odds

On July 21, 1898, two months after construction began, the railroad’s first engine went into service over the first four miles of completed track. The WP&YR was the northernmost railroad in the Western Hemisphere.

Building the one hundred and ten miles of track was a challenge in every way. Construction required cliff hanging turns of 16 degrees, building two tunnels and numerous bridges and trestles. Work on the tunnel at Mile 16 took place in the dead of winter with heavy snow and temperatures as low as 60 below slowed the work. The workers reached the summit of White Pass on February 20, 1899 and by July 6, 1899 construction reached Lake Bennett and the beginning of the river and lakes route.

While construction crews battled their way north laying rail, another crew came from the north heading south and together they met on July 29, 1900 in Carcross where a ceremonial golden spike was driven by Samuel H. Graves, the president of the railroad. Thirty five thousand men worked on the construction of the railroad – some for a day, others for a longer period but all shared in the dream and the hardship.

The $10 million project was the product of British financing, American engineering and Canadian contracting. Tens of thousands of men and 450 tons of explosives overcame harsh and challenging climate and geography to create the “Railway Built of Gold.”

Life After The Gold Rush

The railroad was operated by steam until 1954 when the transition came to diesel electric motive power. White Pass matured into a fully-integrated transportation company operating docks, trains, stage coaches, sleighs, buses, paddle wheelers, trucks, ships, airplanes, hotels and pipelines.

World metal prices plummeted in 1982, mines closed and the WP&YR suspended operations. It reopened in 1988 to operate as a narrow gauge excursion railroad.

The Adventure Continues

The end of the story of one of history’s dynamic events: the Klondike Gold Rush.

One hundred thousand men and women headed north but only 30,000 or 40,000 actually reached the gold fields of the Klondike. Four thousand or so prospectors found the gold but only a few hundred became rich.

What about the discoverers of the gold? George Carmack, Skookum Jim and Dawson Charlie! Carmack’s gold allowed him to have a more adventurous life with two wives, and investment in real estate in Seattle and California. Dawson Charlie sold his mining properties and spent his years in Carcross.

Skookum Jim continued as a prospector and died rich but worn out from his hardy life.

For one hundred years the White Pass & Yukon Route has been an economic lifeline to the north. Freight and passengers moved about the north with ease and the railroad adapted to the changing times. It was the ability to adapt that kept it going – from freight, stampeders and gold to movement of ores and concentrates to tourism – each has been embraced and has given the railroad a new mission in the north.

“On To Alaska With Buchanan”

For fifteen years groups of approximately 50 young people, mostly boys, made the annual summer excursion from Detroit to Alaska. The travelers departed from Detroit in mid-July traveling first class by train across Canada to Vancouver B.C. and Puget Sound. Three days on a steamer and then arrival in Skagway. They boarded the White Pass & Yukon Railroad to travel to the lake country and then a transfer by boat to Atlin.

The young folks, dressed in coat and tie, had to be on their best behavior. Many years later members of the various Buchanan Boys groups returned to Skagway to ride the WP&YR and to revisit the memories of their special and happy trips. Reportedly the boys from one of the summer trips painted the sign “On To Alaska With Buchanan” on the side of the mountain to commemorate their inspiring leader, George Buchanan.

Vision Triumphs over Challenge

Because of this uncertainty the White Pass & Yukon Route decided to incorporate construction in three companies so that the laws of the USA and Canada were obeyed. In Alaska, the railroad was incorporated as Pacific and Arctic Railway & Navigation Company and today still operates under that legal identity. The British Columbia Yukon Railway Company and the British Yukon Railway Company were incorporated in British Columbia and Yukon respectively, with all three companies incorporated in 1898. White Pass & Yukon Route served as an umbrella to coordinate the three entities’ operations.

During the twenty six months of construction the company was challenged by climate, geography and labor issues – all of which translated into soaring construction costs. Nearly all the work between Skagway and the Summit was through solid rock. Dynamite had not yet come into use and immense quantities of black powder were used for blasting. The mountain sides were so steep that the men had to be suspended by ropes to prevent them falling off while cutting the grade. During construction, 35,000 men worked on the railway, and 35 lost their lives.

But Close Brothers of London, under the leadership of W.B. Close, stayed the course, spent $10,000,000 on construction of the railroad. Close Brothers owned White Pass & Yukon Route until 1951 when it was sold to Canadian investors. Close Brothers prospers still today as the largest independent quoted merchant bank in the UK and one of the 200 largest companies by market capitalization listed on the London Stock Exchange.

Skagway

Skagway got its name from the Tlingit (Indian) name “Skagua” which means “the place where the north wind blows”. The maritime climate brings cool summers and mild winters. Average summer temperatures range from 45º-67º F.; winter temperatures average 18º-37º F. Within the shadow of the mountains, Skagway receives less rain than is typical of Southeast Alaska, averaging 26 inches of rain per year, and 39 inches of snow.

The first non-Native settler was Captain William Moore in 1887, who is credited with the discovery of the White Pass route into Interior Canada. In July 1897, gold was discovered in the Klondike, and the first boatload of prospectors landed. By October 1897, according to a Northwest Mounted Police Report, Skagway “had grown from a concourse of tents to a fair-sized town with well-laid-out streets and numerous frame buildings, stores, saloons, gambling houses, dance houses and a population of about 20,000”.

Skagway became the first incorporated City in Alaska in 1900; its population was 3,117 at that time, the second-largest settlement in Alaska.

Skagway is now a restored gold rush town and headquarters of the Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park.

For more information on Skagway visit www.skagway.com.

Living History

In September of 2002, Earl F. Benedict came to Skagway by cruise ship and rode the White Pass & Yukon Route for the first time. He was retracing the steps of his grandfather, who worked for the WP&YR more than a hundred years ago.

While reading the All Aboard magazine, he saw a photo of his grandfather which he had seen in his family’s photo albums! After the train ride, Earl came into the WP&YR offices to share his stories and memories.

Upon returning home, Earl reviewed some of the historical artifacts in his possession and made copies of rare photos and documents for the WP&YR.

Earl Benedict’s visit to Skagway began a new relationship that helps celebrate the living history of the WP&YR!

Maintenance Of Way

Track maintenance using specialized equipment is an important job for WP&YR.

Tamper: picks up the rail as metal teeth vibrate into the ground to pack the ballast, (right of way gravel). Also works as a liner, which uses lasers to indicate track level and curvatures.

Ballast regulator: distributes the ballast evenly and brushes the track after the job is done.

Tie crane: inserts and extracts the ties.

Casey car: used to inspect the line every morning for clearance to begin the day’s excursions.

Michael J. Heney

The partnership between Heney and the men who would become his friends and colleagues in the construction of the railroad was successful. The White Pass & Yukon Route was built in twenty-six months for ten million dollars. The “Scenic Railway of the World” secured Heney’s place in history.

Pay Dirt!

In only five months, between July and November of 1898, the United States mints in Seattle and San Francisco received ten million dollars worth of Klondike Gold. By 1900, another thirty-eight million had been recorded–the result of the largest gold rush the world has ever known!

Railroad Builders

Samuel Graves was president of the railroad from 1898 until 1911. He worked with the Close Brothers Bank of London to finance construction. John Hislop and E.C. Hawkins were surveyors and design engineers for the construction. Michael J. Heney was the labor contractor and manager of the workers who placed the dynamite, laid the rails, built bridges and tunnels and made the dream into reality.

Rolling Stock

The WP&YR rail fleet consists of twenty diesel-electric locomotives, 69 restored and replica passenger coaches and two steam locomotives. The diesel-electric locomotives are General Electric units dating back to the 1950s and ALCO units from the 1960s.

The pride of the fleet is Engine No. 73, a fully restored 1947 Baldwin 2-8-2 Mikado class steam locomotive and was joined by No. 69 in 2005, a Baldwin 2-8-0 built for WP&YR in 1907.

The WP&YR passenger coaches are named after lakes and rivers in Alaska, Yukon and British Columbia and are on average 49 years old. The oldest car, Lake Emerald, was built in 1883 and is on the line each day. Lake Tutshi, vintage 1893, starred in the 1935 Universal Studios movie “Diamond Jim Brady.” And the Lake Lebarge carried Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip on a royal tour out of Whitehorse in 1959.

Rotary Snowplow No. 1

Rotary Snowplow No. 1 was built in 1898 by the Cooke Locomotive and Machinery Company of Paterson, New Jersey for WP&YR.

It helped the railroad face the challenges of heavy winter snows with accumulations of up to 12 feet. Pushed by up to 2 helper engines, the rotary’s 10 huge blades sent snow flying out to the side of the tracks by centrifugal force. It was retired in 1965 but was used as recently as 2001 for a ceremonial clearing of the rails. Rotary Snowplow No. 1 has been restored and can be seen by the Skagway Depot.

The White Pass “Spirit”

The White Pass & Yukon Route (WP&YR) is symbolic of triumph over challenge. The railroad was considered an impossible task but it was literally blasted through coastal mountains in only 26 months over a century ago. Tens of thousands of men with picks and shovels and 450 tons of explosives overcame harsh climate and challenging geography to create “the railway built of gold”.

But, the zenith of the Klondike Gold Rush had passed by the time the railroad was completed. Despite conquering the significant snowfalls with the rotary snowplow and spanning Dead Horse Gulch with the tallest cantilever bridge in the world at the time, it was time to diversify to survive. The WP&YR evolved to encompass wharves, stage lines, paddlewheelers, hotels, aircraft, buses, pipelines, trucks and ships to cater to emerging market conditions.

Self-sufficiency and the need for continuous progress made innovation a hallmark of WP&YR operations. WP&YR pioneered the “Container Route” – the inter-modal movement of containers by ship, train and truck in 1955. In 1988, the company reinvented itself as a tourist attraction for a tourism market after shutting down as a fully integrated transportation company 7 years earlier.

Since 1898, WP&YR’s survival and prosperity has been based on the spirit of accomplishment in the face of adversity.